The focus on algorithms as answer finding tools in K-12 classrooms has resulted in generations of largely mathematically illiterate students. It is less that this approach works for a rare few, and more that a rare few manage to learn mathematics in spite of how terrible algorithms are as teaching tools.

Instead of algorithms, which function as a way for students to get answers without understanding either the process they are using or the answer they get, mathematics that is worth the time it takes to teach depends on developing mathematical reasoning–the ability to use what a student already knows to develop solutions for what they do not yet know. (IES 2025) This is the essence of the work mathematicians do, and it is almost wholly absent from the current K-12 mathematics classroom experience. In other words, the majority of students graduate high school with a distorted view of what mathematics even is.

This mathematical reasoning is best developed through a focus on the Major Strategies (Harris, 2025). This finite list of mathematical problem solving approaches defines the major mathematical relationships that lead to the methods of reasoning a student needs access to in order to progress from counting, to addition and subtraction, to multiplication and division, to proportions, and finally to functions.

This list of major relationships that lead to strategies consist of ideas like:

- Getting to a friendly number

- Overestimating and adjusting

- Creating an equivalent problem that’s easier to solve

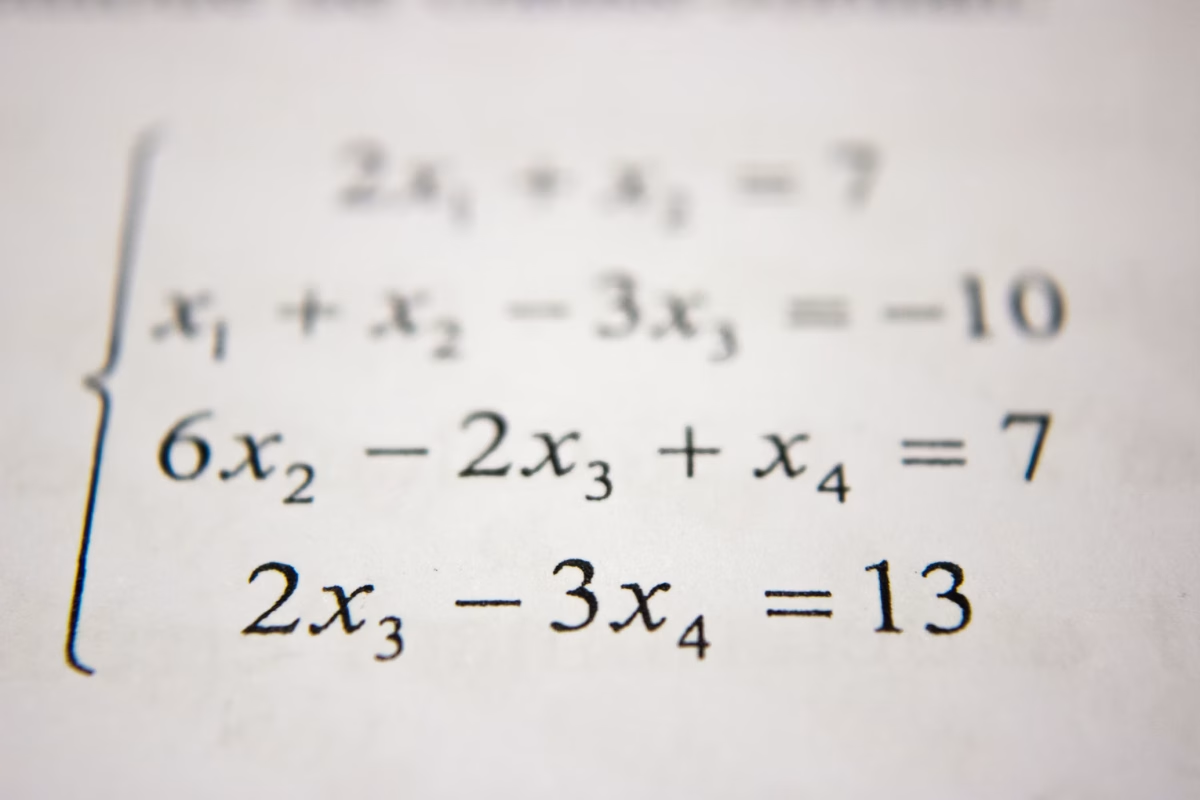

Figure 1. The Development of Mathematical Reasoning

Teachers of mathematical reasoning require a baseline level of mathematical reasoning. Not through any fault of their own, this is often absent. It plays out as a multi-generation bad game of telephone, with each generation resorting to more and more tricks to get answers because they cannot rely on the mathematical reasoning they were never taught.

This is not to say that algorithms in their proper place are a mere trick. Algorithms are amazing human achievements and immensely powerful and useful as general solutions for computers to use. Mathematicians themselves almost never use algorithms to get answers to the one-off kinds of problems in textbooks (Dowker,1992). In the sphere of the K-12 mathematics classroom, algorithms are deadening and inhibitive–they are terrible teaching tools. They become the worst kind of trick, a trap. It is true some learners are able to transcend those limitations, but even they would have done better to be instructed in mathematical reasoning instead of being left to stumble across it by accident.

Algorithms trap students from progressing in at least three general ways, one of which is the digit oriented trap. This means that the traditional algorithms trap students into viewing numbers as lists of digits instead of considering and operating on the magnitudes (sizes) of the numbers.

For example, consider 99 x 27. Students could develop multiplicative reasoning as they grapple with 99 27s, by realizing that it is really close to 100 27s, and reasoning from there that you’ll need one less 27, so 2700 – 27 = 2673. Instantly we have a good approximation and students’ brains get the mental exercise of dealing with the actual values in the problem.

However the traditional algorithm has students consider the digits 9, 9, 2, 7. Then students:

- perform several single-digit multiplications,

- write down those answers as digits,

- add the rows in columns of digits.

- treat every number in those steps as digits, digits, digits

Another aspect of this trap is that the digits are used in the least intuitive order. If a student is thinking about 99 27s or 27 99s, they are reasoning about almost 100 27s or they might think about a little less than 30 99s. They never develop a sense of the -ish answer, a sense of reasonableness (Boaler, 2024). But the traditional algorithm starts with 7 x 9, the smallest and least consequential numbers in the problem. This works against students’ intuition, sending the message – don’t think in math class, do steps whether they make sense or not, math is about mimicking, not reasoning.

Problem Strings like the following help give students the necessary high doses of mathematical patterns so they can reason appropriately. The teacher gives the class each problem one at a time, then represents student thinking using a mathematical model, crafts conversations about the important mathematics, and helps students draw important conclusions.

10 x 27 If one pack of gum has 27 sticks, how many sticks are in 10 packs?

9 x 27 How many sticks are in 9 packs? Did anyone use the 10 packs to help?

100 x 27 How many sticks are in 100 packs?

99 x 27 How many in 99 packs? How do you know? Did you use 100 packs? Could you?

50 x 27 How many in 50 packs? Just half of 100 packs?

49 x 27 How about just 49 packs? How could you use the 50 packs?

How could you reason about finding 49 packs no matter how many sticks are in those packs?

Students talk about how 9 groups is just one group less than 10, 99 groups are one less group than 100, 50 groups are just half of 100 groups. They are now primed to generalize reasoning about 49 groups, just one less than 50.

In this way, the development of mathematical reasoning becomes a question of equity. The current approaches work–barely–only for the most advantaged students, only those who possess the elusive, ill defined, and deficit-thinking-rooted “math gene.” The reality is that the processes of learning and figuring used by those currently successful in mathematics can be taught to every student. Math is Figure-out-able!

References

Boaler, Jo. Math-Ish. Finding Creativity, Diversity, and Meaning in Mathematics Publisher: HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. 2024.

Dowker, A. (1992). Computational estimation strategies of professional mathematicians. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 23(1), 44–55.

Harris, Pamela Weber. Developing Mathematical Reasoning: Avoiding the Trap of Algorithms. Corwin. 2025.

IES. (2024). Development of mathematical reasoning. Retrieved Jan 27, 2025, from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/infographics/pdf/REL_SE_Development_of_Mathematical_Reasoning.pdf

菱形威而鋼 / October 10, 2025

dsgsdagasdggdsasgdgsdagasdgsagdsa 日本藤素官網

/

misael holland / October 8, 2025

I learned something new today. Watch bbc com persian — in‑depth reports and documentaries. live bulletins and interviews. live updates, analysis programs, talk shows. reliable HD stream on any device.

/