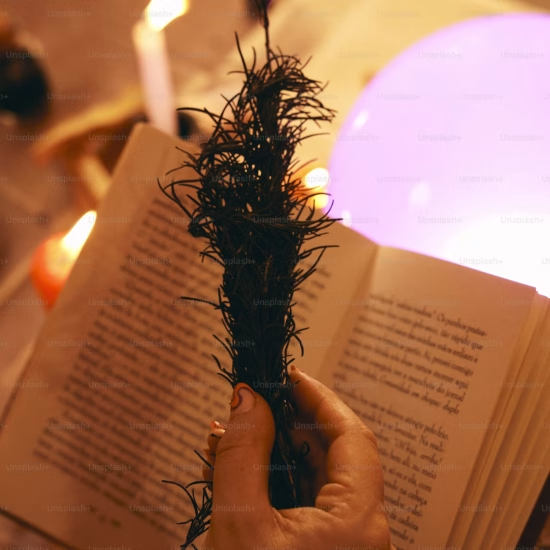

Art by Anzia Anderson from Teaching Fantasy Writing by Carl Anderson

Teach fantasy writing? Why?

It’s undeniable that many children want to write fantasy. Rarely, however, is a study of fantasy writing included in school curriculums.

We can’t blame this omission on writing standards. In the U.S., every set of standards that I’ve seen includes the goal that students will learn to compose well-written narratives. These narrative standards usually state that children can write “real or imagined stories” (emphasis added) to accomplish this goal.

My years of research into teaching students to write fantasy—which led to writing my book Teaching Fantasy Writing: Lessons that Inspire Student Engagement and Creativity—have given me insight into why children aren’t often given the opportunity to write fantasy in school. A major reason is because educators don’t realize the powerful ways fantasy writers—children and adults—use the genre to explore themes and ideas of the utmost importance to themselves and the real world.

For example, C.S. Lewis, whose Narnia books have been beloved by children for decades, explored personally relevant and timely themes in the series. As a boy in Belfast, he and his brother would spend rainy afternoons sitting in a large wardrobe in his home telling each other stories about a magical kingdom they created filled with talking animals. Many years later, Lewis, then a professor at Oxford, housed several of the 800,000 children and teenagers who were evacuated from urban areas during the German bombing of Great Britain during World War II. Likewise, the four Pevensie children—Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy, the main characters of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe—were evacuees from London during the Blitz. In the book, Lewis draws from his childhood experience as he tells the story of displaced children at a time of great stress and danger who travel through a wardrobe into Narnia, a magical land populated by talking animals, to become part of a great struggle between good and evil (Lex 2018; Lindsley 2005). Why write The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe? It gave Lewis the opportunity to explore imagination and storytelling’s critical roles in coping with and surviving traumatic situations.

When children write fantasy, they likewise use the genre to explore personally important themes. Their stories about magical settings and fantastical creatures have so much more meaning than may be obvious on the surface.

In the primary grades, it can be a challenge for children to develop relationships with people outside their immediate family; the process of making friends often creates anxiety! Lana, a kindergartener, explores the theme of relationships by writing a story about Stela, a girl who is “sad very sad” because “nobody wanted to play with her!” Stela finds a magic door and enters a magical land where she encounters a bunny. Initially, she’s not sure how she feels about the bunny (“Stela did not like the bunny following her”), but they eventually become friends (“They played games all day. Oh-my-gosh”).

We can read Lana’s story as her way to process the social aspects of her kindergarten experience. After all, aren’t the doors of an elementary school portals of sorts that transport children into the magical world of school? A world in which children will sometimes feel sad and lonely—and in which they ultimately learn to make new friends?

In the upper grades, students are curious about the outside world and are starting to chafe at the restrictions placed on them by their parents. In “Flames of the Soul,” a story written by fourth grader Gabriel, the main character Triton tries to leave his village—which no one has left for 200 years—but is thwarted by his father. When evil wizards attack the village, Triton must leave the village and use his magical powers to defeat them. Although successful in his quest, Triton experiences significant personal loss. When he returns to the village, he has a new appreciation for it (“I’ll never take it for granted again”).

“Flames of the Soul” reads as Gabriel’s way of processing the changes upper elementary grade students face in their lives. Through writing about Triton, Gabriel imagines a space in which it’s possible to enter the outside world and navigate its challenges, even though they may bring some hardships. He also imagines that it’s possible to do so while holding on to an appreciation of one’s family.

Children of all ages must sometimes deal with the loss of a loved one. Third grader Sanaa dedicates her story “Ellie’s Unicorn” to her cousin, who lost her mom. In the story, ten-year old Ellie, whose mom has died, goes through a magic portal. She meets a unicorn named Luna with the power to bring back deceased relatives for 24 days. Luna brings Ellie’s mom back to life, and Ellie is “happy because . . . she knows when to say goodbye.”

In “Ellie’s Unicorn,” Sanaa explores a theme of great personal significance: How does one deal with the death of a loved one? Through writing the story, she comes up with an answer—that you can imagine having conversations with that loved one and that those conversations can help you say goodbye and come to terms with your loss. That these conversations have a time limit of 24 days (in fantasy, magic often comes with limitations) speaks to the universal need we all face to eventually move on, and to the promise that it will be possible.

During my research, I did many residencies in K-8 classrooms, where I helped lead studies of fantasy writing. Through this work, I had the opportunity to work with the students I’ve profiled in this blog—and many others who similarly used fantasy writing to explore personally significant themes. Students enthusiastically wrote gripping, evocative fantasy stories dealing with bullying, overcoming low self-esteem, finding the confidence in oneself to take on important projects, fighting injustice, and more. As they did so, they learned how to write great leads to draw in the reader, create and describe characters and settings, develop a narrative arc for their main character, and many other crafting techniques.

When you teach fantasy writing, you’ll be amazed as you make the same discoveries that I did about this incredible genre. Fantasy opens up creative and emotional spaces for students, magical doors you might say, that would otherwise remain closed. It’s a genre that gives students the tools they need to explore significant themes they might very well never write about in other genres.

Learn about how to teach fantasy writing in Carl Anderson’s book Teaching Fantasy Writing K-6: Lessons that Inspire Student Engagement and Creativity. The book includes ready-to-go fantasy writing units for grades K–1, 2–3, and 4–6.

References

Lex (2018, September 2). Interpreting The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as World War fiction. Hope and Whispers. https://hopeandwhispers.wordpress.com/2018/09/02/interpreting-the-lion-the-witch-and-the-wardrobe-as-world-war-fiction/

Lindsley, A. (2005, December 5). The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: Lewis’s best-loved classic. C.S. Lewis Institute. https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/resources/the-lion-the-witch-and-the-wardrobe/

日本藤素ptt / October 10, 2025

t with its smooth interface and great game variety-from slots to live dealers. Their step-by-step setup makes it easy for new players to get started. 威而鋼購買

/

犀利士藥局 / October 10, 2025

s out with its smooth interface and great game variety-from slots to live dealers. Their step-by-step setup makes it easy for new players to get started. 奇力片哪裡買

/

amber valdez / October 8, 2025

This helped me a lot, thank you. Go live with bbc news urdu today — regional coverage for Iran and Afghanistan. live bulletins and interviews. feature stories, talk shows. Including today’s schedule. clean player and fast startup.

/

shi changao / July 23, 2025

Real-time updates are a huge advantage when managing a site. It’s just as efficient and user-friendly as winspire88.

/

shi changao / July 23, 2025

Love how easy it is to make changes on the fly! That same kind of smooth experience is exactly what winspire88 offers to online gamers.

/

Miss Gaming / July 13, 2025

Fantasy writing opens up a world where students can explore meaningful themes in creative ways. Just like how Buenas Gaming offers immersive experiences that engage players deeply, fantasy storytelling helps learners connect personally while building their skills.

/

JiliOK / May 26, 2025

JiliOK Casino blends art and analytics beautifully-its AI-driven approach is a game-changer. The platform’s seamless mix of slots, live games, and intuitive design makes it a top choice for Filipino players. Check it out at JiliOK Casino!

/

Top AI Tools / May 24, 2025

This breakdown hits all the right marks-deep insights, clever angles, and that surprising twist that keeps you hooked. For AI powered game analysis, Top AI Tools is a goldmine for finding the next big thing in tech.

/

💾 + 1.364336 BTC.GET - https://yandex.com/poll/5JjqQt7R61CTYdYVd17t6p?hs=2fc98729a1b2e20df195d22b1c6a7cc1& 💾 / May 23, 2025

x7r2hl

/

JLJLPH / May 22, 2025

I’ve tried a few platforms, but JLJLPH stands out with its smooth interface and great game variety-from slots to live dealers. Their step-by-step setup makes it easy for new players to get started.

/