Inquiry classrooms are magical places; creative, student-driven, and dynamic. But when it’s only the lesson you see unfolding, you’re missing half the show. For years, I’ve focused my coaching work on the pedagogy of inquiry, trying to demystify what inquiry looks like in real classrooms.

While it’s not as fun perhaps to write (or read) about what happens at the planning table, we cannot pretend that the magic of inquiry-classrooms just happens, well, magically. Planning for inquiry reminds me of the proverb: A river needs banks to flow. I see my lesson planning as creating the proverbial ‘banks.’ These banks provide the space and order necessary to encourage the freefall of ideas, divergent questions, and cognitive dissonance to take place.

In fact, I’ve found that lesson planning is the most creative part of my job. I’ve learned to embrace rather than dread it using this simple 5-Step Inquiry Lesson Plan.

Step 1: Connect with and question the content as a person, not as a teacher

Take off your teacher hat for a moment. How can you strengthen emotional bonds with and between your students within the context of this lesson? How can you share your own curiosity, doubts, and personality with students using the lesson as a vehicle? If the content isn’t important, fascinating, and/or relevant to you, it’s unlikely your students will find an emotional connection to it either.

- What questions still perplex and fascinate you?

- What relevant stories can you tell relating to the content?

- Are there metaphors that might be helpful to students?

- Do you remember the first time you learned this yourself?

- Are there websites that explore these questions and ideas in greater detail?

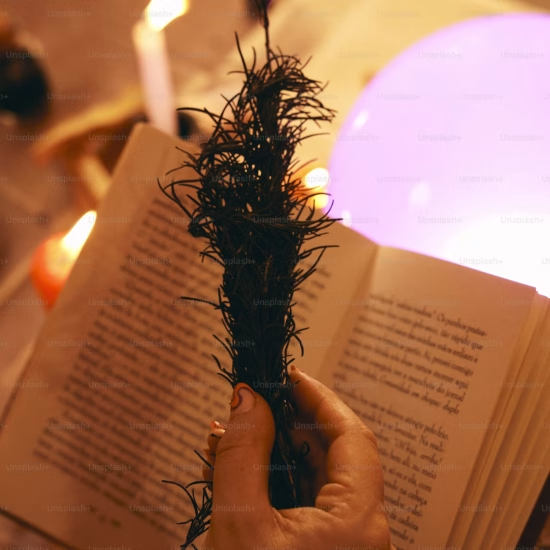

Here’s how I might approach the first step for an upcoming lesson. Let’s say I’m teaching Shakespeare’s Macbeth and we’re on Act IV, Scene I[1]. You may remember this scene by its opening line: “Round about the cauldron go…” or it’s repeated chorus: “Double, double, toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble.” It’s an entire scene where witches create a complicated spell; full of challenging vocabulary and foreshadowing.

| My emotional connection to the content:

This scene is bursting with gross, descriptive words—a recipe for disaster! It reminds me of potions class from the Harry Potter series. My husband is a former chef and he always talks about the importance of getting the right ingredients. The process involved here reminds me of him in the kitchen; so incredibly detailed and painstakingly precise. My lingering questions and wonders relating to the content:

Resources that will provide reliable and diverse perspectives on the content:

|

This ‘emotional brain dump’ was fun and took me no more than five minutes to accomplish. To get the students to connect with one another, I’ll ask them to share their favorite dishes and analyze the ingredients that go into them (thinking about the role of ingredients in making a dish or a charm so special and memorable).

Step 2: Get clear on the goals and assessments

This is usually where we start when lesson planning: our objectives. Think about what you want students to get out of your lesson, and how you might measure these goals (even imperfectly). What mix of formative assessments will you use? Are there authentic assessments (products, performances or presentations) that you can use to motivate them individually or in teams? What do you want students to know (content), be able to do (skills), and/or believe (dispositions) by the end of this lesson or unit?

Again, using the Shakespeare example, I might choose the following mix of content and skill-related objectives for my lesson. I try not to list more than five main objectives so that I can stay focused (less is more). I also really try to make sure I balance the knowledge, skills (especially communication, critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration) and dispositions (patience, empathy, growth mindset) when listing out my objectives.

| What will students know, do, and believe?

(Knowledge, Skills, Dispositions) |

How will we know we’ve achieved this?

(Assessments) |

| Understand the scene’s meaning (knowledge) | Ingredient Analysis and Questions group presentation; listening in on conversations |

| Take risks with ideas; communicate clearly

(skills) |

Observations and student reflection survey |

| Back up conjectures with evidence (either from text, experience, or websites) CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.1

(skills) |

Ingredient Analysis (source citations) |

| Gain confidence and interest in tackling challenging texts like this one (dispositions) | Student reflection survey |

Step 3: Design the lesson and plot questions

Once I have a sense of the why and how, I am ready to create the ‘flow.’ This is where traditional lesson planning comes in. What’s your hook or anticipatory set? How much time do you think you’ll need to provide instruction before releasing students? Will assignments be rigorous enough, but not completely out of reach? Will students be grouped together, when and how? How will students be held accountable for their work?

As you go through the lesson sequencing, you’ll want to simultaneously think about the driving questions for this lesson (in the event that students don’t raise these questions on their own during the lesson), as well as ‘pivot questions’ that you can use to transition students to new activities or discussions. These questions are the ones you want students to really take time to think about. I often transfer these onto notecards and post them on the wall during a lesson and take them down as we address them. Students now alert me if there are questions still up on the wall.

Step 4: Check for questions, voice, and choice

After mapping out the lesson flow and the driving questions, I go back through it to check for two important things: opportunities for student questions and student choice.

Now, look back through each of your activities to make sure you’ve created time and opportunities for students to ask questions and make choices. Student voice (question-asking) and student choice are the bedrock of inquiry classrooms, so make sure you’re providing space and structure for these things. In my own lesson planning, I’d place an “X” next to activities that explicitly provide this. There is no rule around how much or how many opportunities you provide, although I’d strive for a 50/50 balance between teacher-directed/teacher talk-time and student-directed/student talk-time.

Again, using the Macbeth example, here is what my lesson plan might look like at this point:

| Activity / Timing | Driving Question(s) | Student Questions | Student Choice |

| Personal Story (10 mins.) | What are the most important ingredients in your favorite dish?

What do recipes have to do with this scene (connection)? |

X |

|

| Reading & Review (5 mins.) | What does this scene leave you feeling?

What questions does it raise for you? |

X |

|

| Group Task: Ingredient Analysis (15 mins.) | How easy, difficult, impossible, and/or immoral would it be to obtain each ingredient here today? |

X |

|

| Small Group Choice (10 mins.) | 1) What’s the most critical ingredient? Why?

2) How would you reverse the charm? 3) What ingredients may be missing? |

X |

|

| Whole Group Sharing (5 mins.) | Which words were confusing and how did you find their definitions?

Which choice question did you choose and what did you come up with? |

||

| Closing (5 mins.) | What kind of ‘prep work’ for the charm needs to happen?

What questions linger? (share my own) |

X |

A Note about Unit Planning

While this plan is designed for a lesson, you can easily adapt it for an entire unit. Rather than plotting out the activities in minutes during Step 3, simply extend them into days.

Great Questions

Questions are the energy source inside inquiry classrooms. Even though I’ve written out driving questions, there should be questions peppered throughout the lesson; coming from me and hopefully the students. I like to share a short list of Great Questions with my students. These questions are great regardless of the content or grade level. They are divergent and encourage clear and critical thinking (and are also perfect for laminating onto desks). These questions are especially helpful when students are leading their own small groups and having discussions together.

| Tell me more… | How did you make that conclusion? |

| What do you think? | How did you get that result? |

| How do you know? | Can you build on what _____ said? |

| Can you summarize what _____ just said? | Who can add to that? |

| Can you put that in your own words? | What are some other possibilities? |

| Do you have anything to add? | Where do those ideas come from? |

| Do you all agree with _____? | Is _____ correct? How do you know? |

| What do you all think about that? | Why? |

Step 5: Rapidly reflect

This step is often ignored, but is a critical part of the inquiry cycle because it requires us as teachers to flex our reflective inquiry muscles! This step shouldn’t require a lot of time, and can always be completed with the students after a lesson or a unit—after all, they’re some of your best evaluators, having engaged in the lesson from start to finish. Set a timer for five minutes and answer two simple questions:

- What went especially well?

- What would I do differently next time?

Here is what I wrote after trying out the Macbeth lesson:

| What went well?

• Great engagement and discussions while sorting ingredients • 20 minutes was perfect amount of time for group projects |

What would I change?

• Allow them to access websites to find definitions (reinforce source-citing) • Groups no larger than 4 people, otherwise students can disengage • Shorten favorite recipe-sharing time |

Going through this process helps me reflect on perennial questions like: Did students pursue the anticipated line of inquiry? Did they latch onto a misconception and refuse to let it go? Was everyone is engaged; how do I know? Did students ask their own questions? Was it enough or too much student choice?

Conclusion

Successful inquiry classrooms may at times appear aimless and perhaps chaotic, but nothing could be further from the truth. Great inquiry lessons are actually some of the most carefully and thoughtfully planned learning events on the planet. Remember that a river needs banks to flow when thinking about guiding student inquiry. Be clear on why the river is flowing, where it’s going, and how it will get there. The Five-Step Inquiry Lesson Plan will allow you to keep your knees bent and not fall over.

To download a template of 5-Step Inquiry Lesson Plan, go to: https://www.inquirypartners.com/new-page-3 and click “Downloadable PDFs.”

[1] This lesson idea comes from Andrew Finley at West Seattle High School

yodbai / October 25, 2025

What’s up all, here every one is sharing these know-how,

so it’s fastidious to read this webpage, and I used to go to see this weblog every day.

/

Denza BD Ultimate Songkhla / October 23, 2025

It’s perfect time to make some plans for the long run and it’s time

to be happy. I have learn this put up and if I may I desire to

suggest you some fascinating things or suggestions.

Maybe you can write subsequent articles referring to this article.

I desire to learn even more issues about it!

/

indonesia vs iraq / October 11, 2025

I’m not a huge football fan, but lately, a lot of my friends have been talking about the national team matches.

Turns out there’s an important match this week — I found the schedule for the pertandingan timnas indonesia hari ini .

Who knows, maybe someone else wants to watch it too

/

Skorkilat / October 4, 2025

Thank you for discussing this topic in detail, very helpful! I have also written a similar discussion with a different point of view, maybe it could be an additional reference in Skorkilat

/

THEKING / September 6, 2025

“Register now at Terataibola and get a special bonus! Winning just got easier!” Hurry up and search directly on Google Terataibola.TERATAIBOLA

/

Alana Lawrence / September 5, 2025

Right as you open this communication, picture your business connecting with potential clients directly via these website contact forms.

Did you know that contact form marketing is one of the most efficient ways to engage with potential customers and create leads?

Contact Form Leads will reach out to potential customers straight through their contact forms, bypassing traditional advertising methods and increasing engagement where it matters most. Our platform is easy to use, highly efficient, and backed by a team of experts dedicated to helping you succeed.

Deliver your custom communication to millions of companies worldwide from just $22.

Get interested visitors, replies, leads, create awareness, make sales.

— Transform your contact strategy today with Contact Form Leads: https://bit.ly/wowcontactform

Let’s boost your brand now.

Should you decide not to receive future messages from this message, please fill the form at bit. ly/fillunsubform with your domain address (URL).

Knesebeckstra?E 49, Bellport, CA, USA, 94934

/

Damian Dean / August 24, 2025

Right as you open this communication, imagine your company reaching potential clients immediately through these website contact forms.

Did you know that contact form marketing is one of the most effective ways to connect with potential customers and create leads?

Contact Form Leads will reach out to potential customers straight through their contact forms, bypassing traditional advertising methods and increasing engagement where it matters most. Our platform is easy to use, highly effective, and backed by a team of experts dedicated to helping you succeed.

Broadcast your custom communication to an extensive network of businesses across the planet from just $22.

Get interested visitors, replies, leads, create awareness, make sales.

+ Elevate your contact strategy today with Contact Form Leads: https://bit.ly/bulkformsubmit

Let’s boost your brand now.

When you wish to stop getting future messages from me, simply fill the form at bit. ly/fillunsubform with your domain address (URL).

Sletten 200, Geneva, CA, USA, 91892

/

TERATAIBOLA / August 20, 2025

This winning result always makes me happy to play hereTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / August 14, 2025

Join us here to achieve success every day, and it’s very funTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / August 8, 2025

all games easy to make money on this blog,funTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / August 5, 2025

always given victory every day, hurry up and join this blog with meTerataibola“

/

Peter Vance / August 4, 2025

Right as you open this communication, imagine your business connecting with potential clients immediately by means of those online inquiry fields.

Did you know that contact form marketing is one of the most powerful ways to engage with potential customers and produce leads?

Contact Form Leads will reach out to potential customers straight through their contact forms, bypassing traditional advertising methods and increasing engagement where it matters most. Our platform is easy to use, highly effective, and backed by a team of experts dedicated to helping you succeed.

Send your custom communication to countless organizations across the planet from just $22.

Get interested visitors, replies, leads, create awareness, make sales.

— Revolutionize your marketing approach today with Contact Form Leads: https://bit.ly/bulkformsubmit

Let’s boost your brand now.

In case you choose to opt-out of any more communications from this campaign, simply fill the form at bit. ly/fillunsubform with your domain address (URL).

2435 Island Hwy, Dryden, CA, USA, 92975

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 31, 2025

Playing at any time always gives you abundant wins on this blog.Terataibola“

/

satriliga / July 30, 2025

satrialiga experience a real and thrilling adventure in the best adventure game

/

satriliga / July 30, 2025

satrialiga experience a real and thrilling adventure in the best adventure game

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 28, 2025

let’s play games here, get big profitsTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 24, 2025

I want to invite you to play here with me, to enjoy the beauty of the gameTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 18, 2025

There are many games that can make money here, visit this siteTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 17, 2025

playing here is so much fun, let’s join hereTerataibola“

/

TERATAIBOLA / July 13, 2025

Enjoy playing on this blog, it’s very easy to find profits hereTerataibola“

/

David C / July 8, 2025

Hello-

Does your company have any equipment you are looking to sell?

– DC-

/

gotobet88 / July 1, 2025

This site truly has all of the information I wanted concerning

this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

/

Ernesto / June 2, 2025

Ernestopro.com offers a fantastic approach to implementing the 5-Step Inquiry Lesson Plan effectively. Its user-friendly platform supports educators in transforming their teaching methods to foster curiosity and deeper understanding among students. I highly recommend ernestopro.com as a valuable tool for every teacher looking to enrich their inquiry-based learning strategies. It truly makes a difference in educational practices.

/

Pingback: Approaching Teaching: Week of August 25, 2019 | Approaching Teaching @ AISK / August 24, 2019

/

Sumna Rizvi / September 28, 2018

Hi! We’re just stepping into PYP as a school. For my personal understanding of how to make a inquiry based plan, I was scourging the net. You deconstructed and explained it so well…feeling motivated to try making one for my class! Thank you!!

/

Kimberly / October 1, 2018

Thanks for the feedback, Sumna! For even more deconstruction and demystification of inquiry as you implement PYP, please check out my new book: Experience Inquiry: https://us.corwin.com/en-us/nam/experience-inquiry/book259906.

/

Michelle Greenfield-Sliwa / August 8, 2018

I can’t access the template – can you provide a direct link?

/

Kimberly L. Mitchell / October 1, 2018

Hi Michelle,

Thanks for reaching out. Here’s a link: https://inquirypartners.squarespace.com/config/pages

Let me know how it works out for you!

Kimberly

/

Kimberly L. Mitchell / October 1, 2018

Sorry – here’s the correct link: https://www.inquirypartners.com/inquiry-lesson-plan-template-1/

/

Kimberly L. Mitchell / October 1, 2018

Sorry – here’s the correct link: https://www.inquirypartners.com/inquiry-lesson-plan-template-1/

/

Sarah / January 29, 2018

Kimberly,

Once again you WOW me with your work. This definitely sums up an exceptional inquiry lesson and is very clear for everyone that reads it. I am going to share this with all IB coordinators in Alberta at our next meeting. Your amazing inquiry techniques resonated with teachers at all levels when you were here. Looking forward to using your book as a book study.Thank you.

/

Kimberly / January 29, 2018

Thank you, Sarah! The book should be out just in time for the start of the 2018 school year. I appreciate your support and look forward to continuing to collaborate with you.

/

Scottie N / January 6, 2018

You have provided such clear support for teachers to be facilitators of learning. These steps can be used in a class period for shorter inquiry or to guide learning for a longer projects. The process is so tightly aligned to best practice – I really appreciate your clarity. Thank you, Kimberly, for sharing!

/

Kimberly / January 7, 2018

Thanks so much, Scottie!

/

Julie Kalmus / January 4, 2018

I love the explicit separation of student questions and student choice. It’s an important distinction and one that I often muddle in my own practice. Thank you for a thoughtful and well-constructed road map!

/

Kimberly / January 4, 2018

Thank you, Julie!

/

Mary Kouyoumdzoglou / January 3, 2018

Kimberly, you have always been a leader in Inquiry. Even works in the primary grades. Best if schoolwide. Wishing your book to be a best seller.

/

Kimberly / January 4, 2018

Coming from one of the best elementary teachers I’ve had the privilege working with, this means a lot, Mary. Thank you!

/

bishnu / April 11, 2019

Hi Kimberly,

Greetings from Nepal,

I am working as a principal in a school where poor and orphan children studying together with day scholars. If you make a little time to visit this country (Nepal) I would love to see you in my school for teachers’ development program. I am looking forward for your positive response.

thanking you

/

Kimberly / September 5, 2019

Hi Bishnu!

I would love to come to Nepal and work with you. Please get in touch with me via email: klasher@mac.com. In the meantime, check out my book, Experience Inquiry. You can get started on inquiry together right away with the exercises.

/

Anne K / December 27, 2017

Thank you, Kimberly, for your thought provoking post. Step 1 is so important! Especially leading and guiding students in their inquiry by establishing a personal connection. That first step gives students the confidence to let their curiosity and questions ebb and flow within the ‘proverbial banks’.

/

Kimberly / January 2, 2018

Thank you, Anne! I agree that Step One is essential (and was never a part of my formal training).

/

Molly Sedlik / December 24, 2017

Finally! A step-by-step guide to put the inquiry wheels into motion. I love the concrete example offered here and cannot wait for Kimberly’s book to come out. Experience Inquiry will be a must-read for all stripes of teachers, parents and community leaders included.

/

Kimberly / January 2, 2018

Thank you, Molly. Connecting this work with non-profit leaders like you and those who work with adults is so important. I appreciate your interest and support.

/

Jodi Haavig / December 23, 2017

Thanks Kimberly for the great reminders and coaching around the importance of deliberate planning for inquiry. Among my key takeaways were to remember to encourage student voice and choice, but to also tend to those river banks and guide the inquiry experience. I’ll also be keeping a few of your “great questions” in my back pocket. Good stuff!

/

Kimberly / January 2, 2018

Thanks, Jodi. The great questions can also be taped onto students’ desks for quick reference. I appreciate your support!

/

kristin McInaney / December 22, 2017

I love this article and will share it with our PBL working group to help us design our intensives for next year.

Thank-you for writing an article that outlines steps.

Kristin

/

Kimberly / January 2, 2018

I’m so glad this will be helpful for your PBL work, Kristin. Let me know how it goes!

/